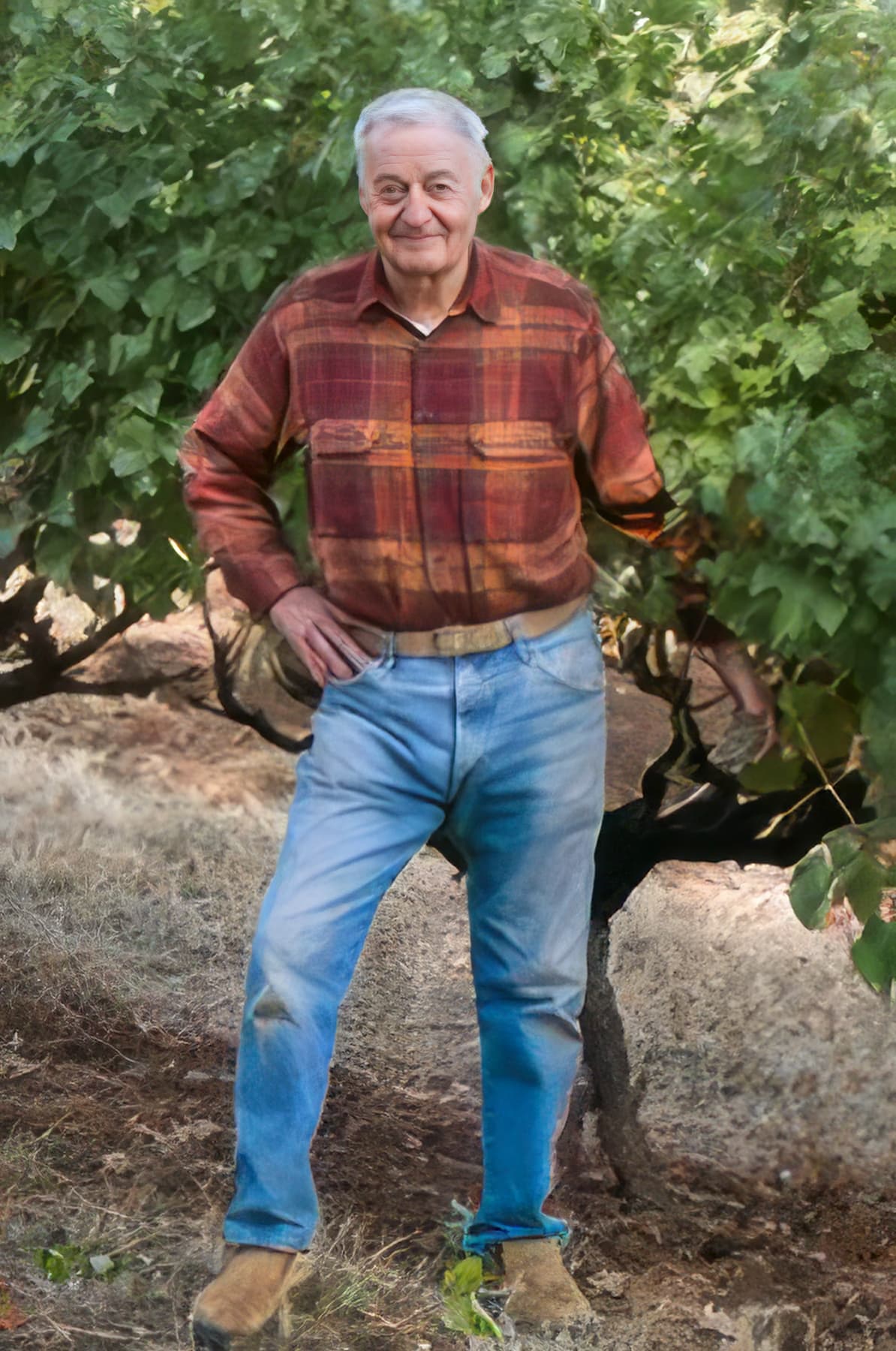

Jim Maresh –

Old Vines Run Deep

September, 2021 –

This harvest has been earlier than ever but of course, the emotions of missing Dad – he passed away earlier this year. I remember working with him, pulling off the grapes for the last 45 years and then filling him in last year of him outside on the porch of our family farm house, intently listening to my harvest report of the tractors, the tonnage, the blocks we’re picking, the brix, the quality of fruit, the number of pickers, the wine quality foreseen, the vintage comparison and the predicted weather for next picking. He always had advice well taken by me with love and respect for his and Mom’s years of farming the orchards and vineyards of our farm.

I miss him and will carry on with the legacy of the Maresh Red Hills Vineyard. Farm established 1959. Vineyards established 1970. – Martha

This article was written in 2019 –

Meeting Jim Maresh is like meeting a slice of Oregon history. He is a force to be reckoned with, one of the pioneers of the Oregon wine industry since planting his first grapevines in 1970. Along the way, he profoundly influenced the direction of Oregon’s future, helping protect Oregon farm laws by pushing through legislation and agricultural zoning protections on both county and state levels.

Beyond all the trappings and tales he is a farmer. It is his care for the land that has built his legacy, and his roots are fully grounded in his 160 acre vineyard in the Dundee hills, the 5th oldest in Oregon.

It’s in the handshake: everything in that first impression. His hands are strong, the nails blunt, with calluses along his palms. They are hands that work hard, and have for years. In Jim’s firm yet gentle handshake is the story of the man.

The Story Begins

Jim Maresh was born in 1926 and grew up outside of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, attending the University of Wisconsin at Madison. In 1944 he joined the Navy and, while at a Prom in Marquette, met Loie, his future wife. They married and had five children together: Jim, David, Martha, Joe, and Mary-Grace. Between 1944 and 1954 his military duties took them all across the country: Wisconsin, Oregon, California, New York, and finally, back to Oregon and a permanent address. Jim began a career as a business analyst in Portland that would continue through 1982, and in 1959, the family moved to the country.

Jim never planned to be a farmer, but he fell in love with the red hills of Dundee. So he moved his family from Portland to a 27 acre farm covered with plum, cherry, and hazelnut trees.

Jim had a support system in place before he got rolling. There was Loie, his ever supportive if slightly dubious wife, and five children with quick hands to use as “free labor.” So armed with enthusiasm and an appreciation for the unspoiled area south of Portland the Maresh family became farmers. (Well, some appreciation. Martha, the middle child, remembers that the move wasn’t easy for five rambunctious city kids and their long-suffering mom. At least not at first.)

Jim laughs when asked if he had any prior agricultural experience. “My only exposure to Agriculture was when I passed the Ag building on the Madison campus!” he says.

Fortunately for Jim, he was taken in hand by the “Wise Old Men” of the Dundee Hills. These were farmers who had been working the land generations before Jim arrived. “They taught me everything about how to farm,” he says.

This training – learning by doing from those who learned by doing – served Jim well. The methods he was given by these farmers are the hard fought, carefully tested secrets of farming the red hills. They taught him how to read the soil and the earth. Emil Sanders and Joe Herring were especially generous mentors, patiently explaining whatever he needed to know.

Jim developed a reputation as a careful, respectful steward of the land. When his mentor farmers retired they were happy to sell their land to him. They trusted him to buy it and treat it right. Over the years, he grew his farm to 160 acres at the top of Worden Hill Road with a spectacular view of the Willamette Valley below. The trust was not misplaced.

Introducing the Vines

“I would have planted vines sooner if I’d known you could grow wine in Oregon!” Jim exclaims. “I didn’t know about the potential!” Part of the delay in the Maresh grape farm may have been due to the fact that when they moved onto their land in 1959 Newberg (the nearest city) was dry. Dry as in Prohibition dry, not lack of rain dry. Nobody thought much of the potential alcohol market for the area. So when he pulled up the prune trees on his farm, Jim planted more cherries rather than looking for other options. Cherries were considered a wise investment. The idea of grapes wouldn’t take root for another 10 years.

The Maresh family were the first in Oregon to convert a working farm to a vineyard. In 1969 they decided to plant a vineyard, and Jim brought thousands of vine cuttings up from California. They pulled up their prune orchard and built a green house to get the cuttings ready for planting.

When he was first starting his grapes, Jim thought of asking his neighboring Orchardists for their experience as growers. It seemed logical to him that he would ask advice from other farmers about growing grapes; after all, it was their advice that had seen him through so far. However, all the Orchardists he spoke to were into cherries, at that time a very profitable business, and weren’t willing to break with the “long game” that was a cherry orchard.

At this point, Jim’s support system expanded to include his friend and neighbor Dick. That is Dick Erath, an engineer and owner of the 3rd oldest vineyard in Oregon, who was just starting his winemaking next door, and was more than happy to throw in his lot with Jim.

Both Jim and Dick were learning as they went along and they made mistakes… like forgetting the drain hoses when they started their cuttings. This omission meant that the cuttings wouldn’t be able to put down roots, not healthy ones anyway – meaning that they weren’t sprouting. Not good!

So all the little vines were restarted: trimmed and replanted once the drain hoses were properly laid down. Even with the potentially disastrous mistake every single cutting took; not one vine was lost.

One year later, in the spring of 1970, out of the greenhouse came the cuttings. They were placed tenderly in the ground and surrounded by a milk carton to act as protection and as a miniature greenhouse. The thousands of cuttings were watered by hand once every ten days, by slowly driving a tank with a hose up and down the rows. This is no mean feat, as there were four acres of newly planted vines, 1.5 acres of Riesling and 2.5 acres of Pinot noir.

Milk Cartons You Say

Why yes indeed, Jim Maresh and Dick Erath did use recycled milk cartons to get their vines growing. It was essentially a question of resources. Getting into wine in Oregon in 1969 was … quirky. Farming vines was a new idea back then.

Jim, Dick, and Loie did everything they could to make do. They opened up milk cartons to act as miniature greenhouses, bought used bean wire to keep the vines straight. They had limited resources and nobody to ask for help. So they did the best they could with what was available; a lot of creativity, a lot of working it out as you went along and a lot of support from family and friends.

Jim twinkles mischievously as he tells me a favorite story. It’s the early 1970s. Jim and Dick have just thrown a huge party to celebrate the first wine off of their Dundee hill vineyards. He tells me they were outside Dick’s house, tipsy on their own wine. Jim tries to thank Dick for his help, saying “I’m glad you knew what we were doing, since I had no idea.” Dick just looks at him and says that it was all bluster, that he didn’t have a clue how everything was supposed to work either. But they had gone and done it all the same!

It’s a picture that stands out clearly: imagine two hard working men, laughing at their own madness under the setting sun. It sounds a bit like a fairy tale, but what a story – a would-be-winemaker and a farmer of cherries coming together and by luck, ingenuity and sheer determination creating two of the greatest vineyards in Oregon.

Dirt N Details

Jim is a farmer, not a winemaker. He knows this, and he is proud of it. He doesn’t want to be mistaken for something he’s not. “I think you really need to have a background in chemistry if you are going to make wine” Jim states. Since that is not his background, he doesn’t make the wine. He grows the grapes and he knows he does it very well.

“Soil is alive” says Jim. In order to grow the best vines it must be treated as such. He sees soil as a “micro-population.” If you protect your soil, keep it healthy and strong, then your crops will be the strongest, immune to many attacks. The Maresh farm is on 12 feet of clay loam. “The soil is down deep, so the roots need to run deep too!” He freely admits that his style of farming might not work on different ground, but for the Oregon red clay of the Dundee hills, his system is perfectly suited.

Jim has what is called a “dry farm.” There is no irrigation for his vines, no watering that occurs aside from what happens naturally. Because the roots are set way down in the deep soil, they draw water from the winter and spring rains and from any water stored underground.

Jim also keeps his vines spaced out. He uses California spacing of 6’x12′. He also only plants 600 vines per acre rather than the more common 1000/acre. He likes the air and the drainage that more space provides. The exposure to air and sunlight helps make his grapes some of the best Oregon has to offer. Why crowd the vines together? Give them space and let them grow!

He is careful to always have a cover crop put in by April 10th each year to protect the moisture retention of the earth. Martha remembers that as children, she and her siblings made forts and mazes in the five foot high red clover growing between the rows. Dry farming is the system that he cherishes. Jim is slightly dismissive of the fancy irrigation systems many new vineyards are so quick to install. “All it takes is a little faith in the hills and care of the vines to be sure that the roots are deep enough to stay strong,” says Jim.

In 2013, at the age of 87, Jim still works the land and is proud of every inch of it, knows every vine and plot inside and out. Like any true farmer he has his favorite spot.

In over 100 acres of land, Blocks 3 and 4 are his favorite. They consist of some of the oldest vines on his property, planted in ’71 and ’74 respectively, comprised of Pinot Noir vines of the Wadenswil and Pommard varieties. The site itself is nice and warm: “A magic spot” says Jim.

He goes on to explain that the pinot noir grapes in general are all different, sort of like his children- a unique style or strength in each block. But 3 and 4 are special because the grapes there are sort of like Loie: mellow, smooth, and feminine. These grapes have unique depths, and make practically perfect wine.

Loie, an Influence not to be Underestimated

Loie is a factor that can’t be overlooked in any story of the Maresh family. She passed away in 1992, but her presence has soaked into every aspect of the farm. She was a driving force, a constant support, a mother to her family and to the land. Jim remembers how she would talk to the vines. She’d scold a slow-grower telling it “look at your neighbor. You should keep up!”

There is a wonderful family photograph from 1969 of Loie and Dick Erath looking at the hundreds of vine cuttings that have just arrived from California. They look terrifyingly much like kindling propped up in the new greenhouse and absolutely nothing like grape vines. She has a resigned expression on her face, prepared for whatever this new adventure will bring. Jim says it looks like she was attending a wake, but I see more true determination.

Loie was a strong woman who took no guff from anybody! “She could spot the phony” says Jim, as he launches into a tale of Loie working their tasting barn back in the early days. Maresh vineyards had just implemented a tasting fee of $1.00. Loie would apologize about it to customers explaining that it “keeps out the Riffraff.”

Well, one day while she was working the tasting counter, a man came in and asked if she could make change for a one hundred dollar bill. He was obviously trying to get her to waive the fee. But every morning the Maresh family would put $100 in change into their till. So she made the change for him. And when he left she made sure to call the other vineyards in the area in case he stopped in one of them to try the same thing!

Loie was a farmer’s wife but also a career teacher. She specialized in helping children learn to read. Jim remains proud that she could take a non-reading child and get him or her up to or above grade level. To this day they have a special fund in her memory. It’s called “Loie’s Wine,” and comes from a block on their land. “Loie’s Wine” is just one barrel a year, but all profits from its sale go to the Dundee Reading Fund.

In true family fashion this wine is nothing to be sneezed at. The 2003 Loie’s Wine was ranked #3 in a list of the 600 best North American Pinots! That year each bottle retailed at $75.00: every penny was donated into her fund. This is the Maresh way of giving back. They have a community of wine farmers that runs strong, but they never have forgotten the Oregon community as a whole.

Keeping the Community Strong – or – “a little-known story about how we preserved the land and we had to fight for it”

Part of building any community is giving back, and Jim has gone above and beyond. He not only helped start the Dundee hills wine community, but he has protected it and the farming community as a whole.

It all began back in 1960 when developers tried to introduce suburban homes to the Dundee hills. Families and neighbors banded together to try and keep them away, claiming that the houses would break down the agricultural structure of the area. The County Commissioners were surprised that the farming families wouldn’t want to “cash in” by selling their land, but they capitulated to the demands of the locals.

Despite the first ruling, County Commissioners continued to try to bring industry into the area. In protest the Mareshes were among three main farming families who went to the Commissioners. Together these families represented a good percentage of acreage in the Dundee Hills, and they asked the commission to set aside their land as an agricultural reserve. This would restrict subdivision possibilities effectively and permanently hold off developers from breaking up farm acreage.

The battle to keep out housing developments at the county level was won. A few years later, in 1973, the land use laws came into effect; officially setting aside the Dundee Hills farmland for Exclusive Farm Use (EFU).

Like anything, the first battle is never the last.

“Industry and Developers never give up” says Jim, laughing. “They are like yellow jackets: they keep coming back around.”

The Asphalt Plant and the Rajneeshpuram

Round two of the battle for Dundee hills began with the innocuous Crabtree Rock quarry. It operated along one edge of the hills during the 1970s and 80s where it produced good gravel. Some developers wanted to change the definition of a quarry to an “industrial zone.” Defining the area as an industrial zone would allow the manufacturing of asphalt.

Jim had a fundamental problem with this. The manufacture of asphalt produces a very strong odor. “A vineyard is like a giant sponge, it just sucks in its environment” he explained to me. If these odors went into the air, it was goodbye to the sweet tasting Dundee Hill grapes, and by this time Jim wasn’t the only wine grower on the hills.

So Jim and the other vintners went to the county to try to protect their vines. The county ruled against them.

Wine farmers aren’t the kind to fold up and let it go, so Jim took his case to the Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC). Jim was helped along the way by his neighbors including the Weber, Stevens, Lett, Archibald and Bower families, Dick Erath, Jim’s own family and the 1000 Friends of Oregon association, which stepped in to help with legal fees.

On the day of the ruling, in December 1982, Jim was in for a bit of a surprise. He showed up to the courthouse to find it surrounded by reporters and TV cameras. They weren’t there for him but for the Rajneeshpuram land use trial that was to follow his case. The reporters showed up early, but they weren’t to be disappointed.

Jim actually took center stage towards the end of the hearing. He tells me, thirty years later, “My attorney just blew it. I could tell the Commissioners weren’t convinced.” So he stood up to say something, anything. He didn’t have a thing prepared but he knew they were losing and he couldn’t bear it. There were seven Commissioners to convince to rule in his favor and the livelihood of Dundee wines resting on his shoulders.

He ended up making quite a case. He pulls his arguments forward again as I listen, rapt as if it was the same day as the trial and I were sitting there in person. I felt like one of the reporters who all sat and listened, taking more notice as the hearing went on. It wasn’t the high-profile Rajneesh case, but many of the reporters could tell that this farmer was full of passion and began to feel for him. Jim noted their growing interest as his speech developed.

Jim began by invoking the rights of an Exclusive Farm Use zone: “You know, we made an investment in viticulture… we did that because we knew we had the protection of an EFU zone. ” He went on to talk about how Ozone stipple (the product of asphalt production) is not compatible with vineyards, how it kills them.

His strongest argument came when he addressed himself to the people of Oregon: “Oregonians are gonna have to make a choice, do they want viticulture or do they want industry? We’ll go plant [our vines] somewhere else.” Vineyards had been a smart investment for farmers to make, and Oregonians were reaping the benefits.

By his very presence, Jim managed to highlight the differences between impersonal business industry and family farming.

The Commissioners voted 6 to 1 for the vintners.

Jim says he was told later that it was thanks to him that they won that day. The Commission had been set against him before the hearing even began. Thanks to his passion, and a lady commissioner who pushed for him in deliberation, he protected the Hills from the asphalt plant.

Yellow Jackets Indeed

Of course Yamhill County appealed! The case ended up in the Oregon State court of appeals as “Maresh et al. vs. Yamhill County.” It was the LCDC which made the decision in favor of the farmers, and they had to defend that position. The Dundee hills families were only spectators. Very happy spectators when in 1984 the Court of Appeals chose to uphold the decision to prevent the manufacturing of asphalt. Then a year later in 1985, there was again the threat of a wording change that would allow the asphalt processing. So the late Arthur Weber and Jim Maresh went to an Oregon senator with their case. This senator was willing to carry a proposed amendment to protect vineyards from asphalt production once and for all.

The Senate approved the Weber-Maresh Amendment which states that “an asphalt batch plant shall not be allowed within three miles of existing vineyards.” This amendment stands even today protecting vintners and their vineyards all across Oregon.

Jim was willing to fight for farmland before there were laws to protect it. He was willing to fight for vineyards to protect the crops he and other farmers were invested in. He was willing to go above and beyond to pass a law that would protect the wine-growers all across Oregon. This man has done more than foster a community of wine. He helped to create it, and then he made sure it was protected. If he is not the father of Oregon vines, he is certainly its Godparent, protecting and sheltering the interest of wine growers and makers alike.

Today Jim says he feels legitimized. They fought a hard fight to get their vineyard to succeed, and now he watches new vintners come in with all sorts of resources right from the beginning. Jim likes to think of it as a community of support, that his hard work helped to build something special that so many people want to be a part of it. These new-comers have this community available now due, in no small part, to the efforts of Jim Maresh and Dick Erath.

Deep Roots: a network of strength, sustenance, and support

Jim Maresh believes that part of why his grapes are so good is that they have taken some of the flavors of their predecessors; all of his wine is grown on land that used to be prune and cherry orchards. He thinks that maybe, just maybe, the flavor of plum and cherry is still in the ground. Some of the old trees’ roots are still down deep, where they have become tangled with the roots of the grape vines. They share the old nutrients of the soil.

He has used the wisdom of old farmers, his grapes taken root in the enriched soil of past farming, the land itself has formed a system of support – one might even say a community. Jim’s grapes grow through his wisdom, through his encouraging them to grow deep and strong, grounded in the hills.

Like his vines, Jim has nurtured the community of wine. With his help the farming of wine took over the Dundee hills. With his support and drive it became protected. Just as the wise old farmers opened their arms to him, Jim has opened the arms of a community to the present and future generations of wine farmers and makers.

He is like an old vine himself, with a root system to support him allowing him to give support and sustenance to those who have come to rely on his strength. Jim, supported by family and friends, will continue to produce good grapes just the same as always.